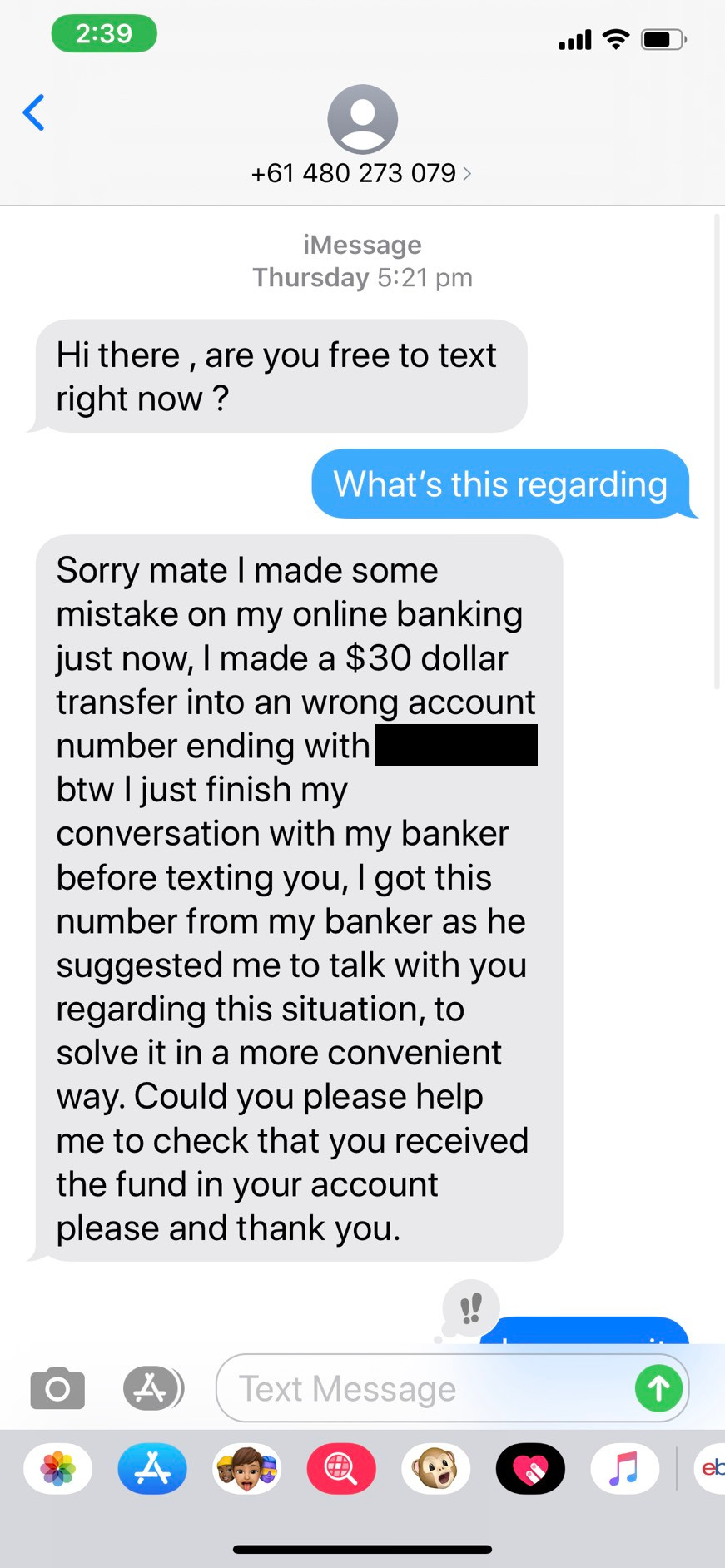

One of my friends recently fell victim to a pretty rudimentary and unremarkable banking scam. Unsurprisingly, he was pretty annoyed, but interestingly, the bank allegedly told him that they had no idea how the attack was carried out with such limited information, and they had never seen this specific M.O..

Now, if you’re anything like me then you probably wouldn’t trust a customer facing branch representative to be the most informed about fraud and social engineering attacks. This led me to do my own little “investigation” (read: googling for a few sources) to try and piece together how attack took place, mostly as a thinking exercise. Let’s take a look at what we’ve got.

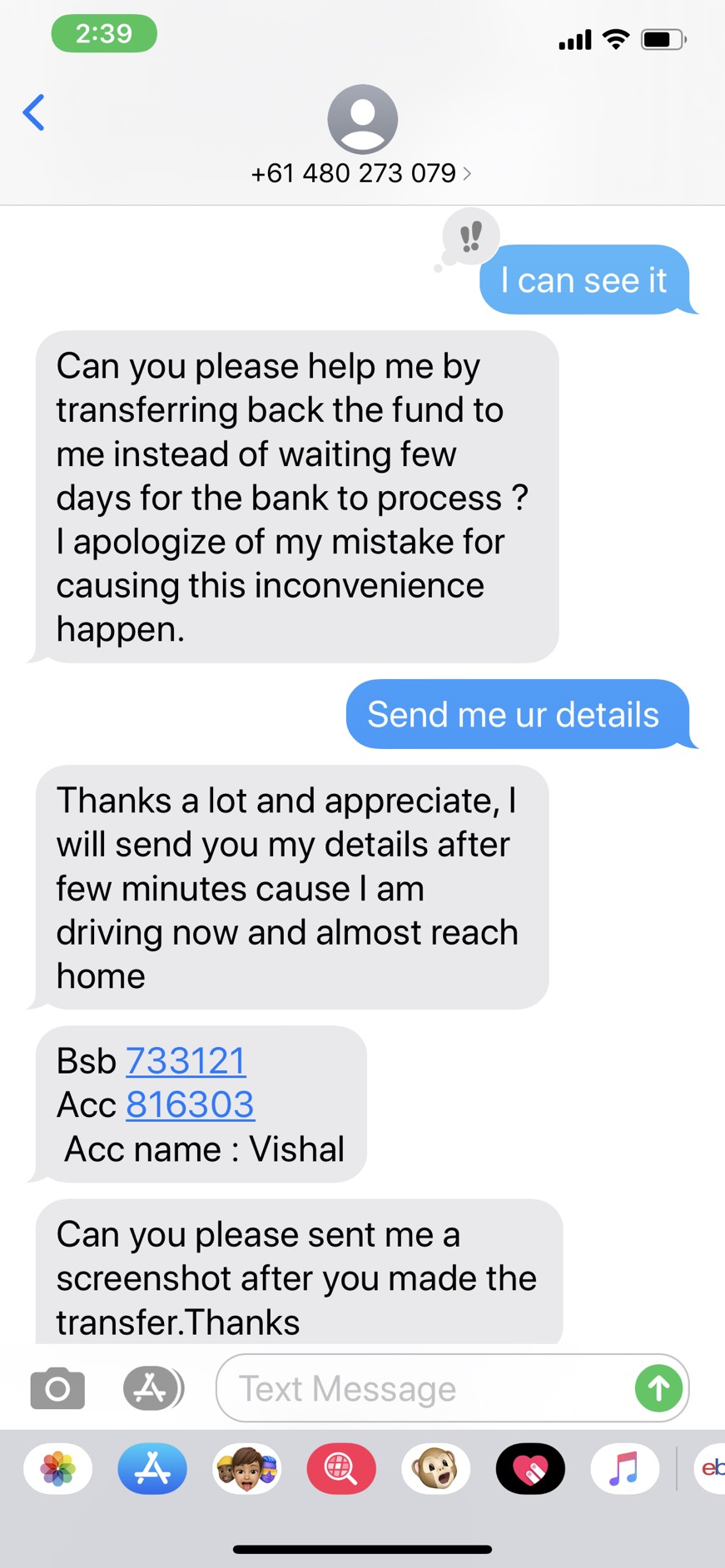

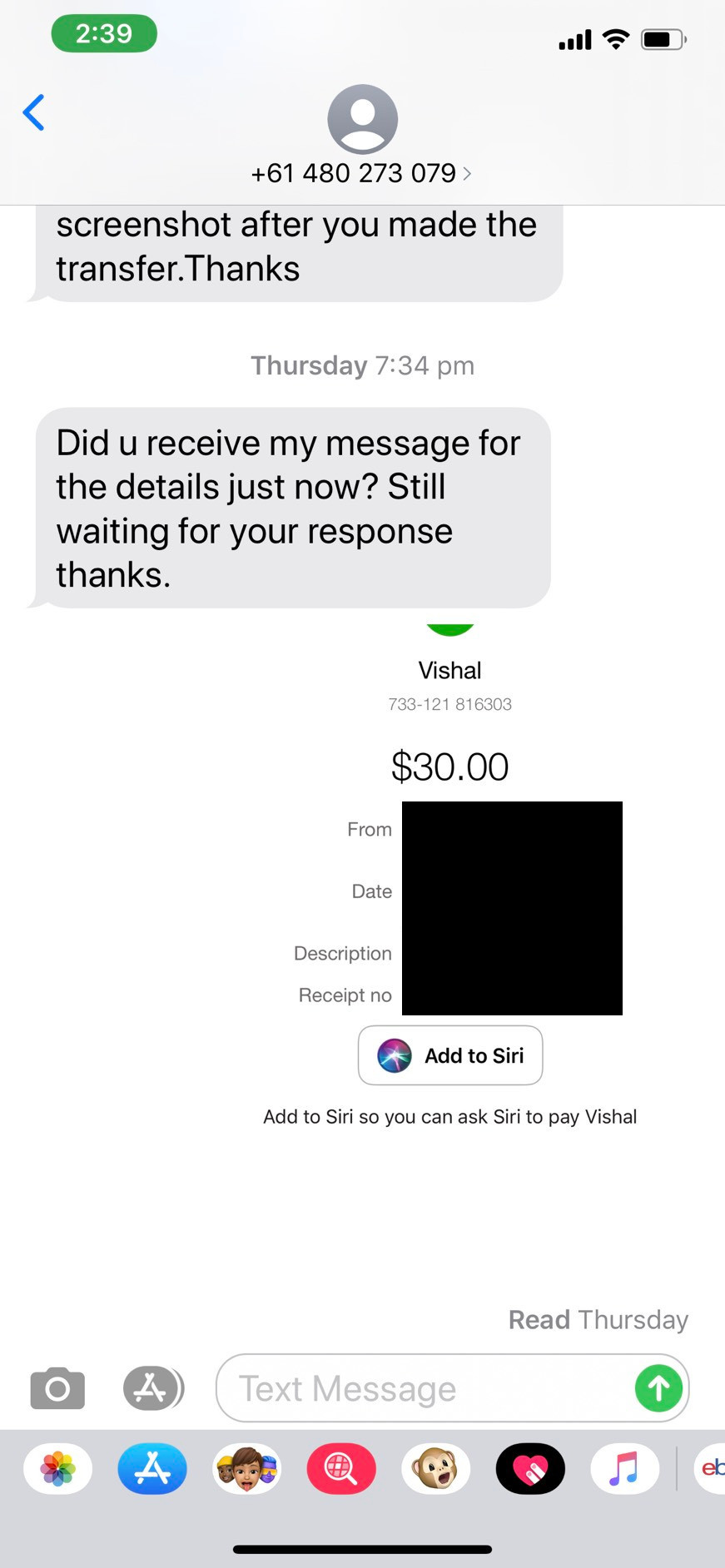

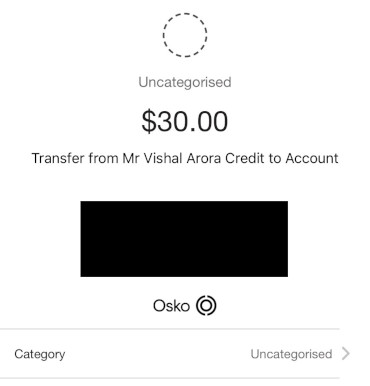

My friend noticed that $30 had indeed been deposited into his account, so he returned the money as requested. Shortly afterwards, he noticed several large outbound transactions from his account. Upon trying to contact “Vishal” again, he discovered that the phone number had been deactivated and he was a large sum out of pocket. All he did was transfer some money; how did the attacker end up authorising multiple deposits?

As a side note, it’s pretty inconvenient to keep saying “my friend”, so let’s call him Kenji from now on. Obviously that’s not his real name, but I may as well do my due diligence to protect his identity. Here’s a picture of him.

Anyway, let’s list out the events in chronological order to help us get a better picture of what’s going on. Then we can dive into each of the individual steps and see if we can figure out how each step was carried out.

- Vishal transferred $30 into Kenji’s bank account.

- Vishal texted Kenji and requested the $30 be returned.

- Kenji transferred the $30 back to Vishal.

- Vishal gained access to Kenji’s bank account and stole all of his money.

Full disclosure, there are a lot of unknowns and I don’t claim to know exactly how any of this took place. Everything on this post is just conjecture. Take it with a grain of salt.

1. The Initial Deposit

Pre-requisite: Branch number (BSB) and account number.

Goal: To plant money into Kenji’s bank account.

This stage is easy. Depositing money into a stranger’s bank account is a trivial matter. BSBs and account numbers aren’t private information. They’re intended to be shared, so that people can send you money. Chances are this was leaked in one (or several) of myriad conversations where it may have come up. Worst case, you can just guess some numbers and eventually send money to someone. In this instance, the money just happened to go to Kenji.

The next part is where it gets a bit trickier.

2. Getting in Touch

Pre-requisite: Mobile phone number.

Goal: To contact Kenji and request a transfer.

To get in touch with Kenji, Vishal needed his phone number. As with before, phone numbers are public information and are intended to be shared. How many times have you given away your phone number to someone? You’ve probably used it to sign up to a number of services, and have totally forgotten about half of them. Can you be sure that none of those people/companies have leaked your phone number? Even unintentionally?

That being said, any old phone number won’t do. Vishal needed Kenji’s phone number specifically. The knee-jerk reaction here is to ask “how did he go from making a deposit into a random bank account to finding the phone number of the account owner?”, and that would be a perfectly valid line of thought. I don’t have a good answer to this, but I don’t think I actually need to. This is where the causality goes a bit backwards, and I apologise for intentionally leading you down this route to make for a more dramatic reveal.

My theory is that Vishal didn’t need to extract a phone number from banking information at all. At the end of the day, he just needs to be able to transfer money to a bank account, and to be able to contact the account owner. Conveniently enough, good old Australian banks have provided a means to do exactly this: PayID.

Instead of entering bank account and BSB numbers — like with a traditional electronic bank transfer — PayID only requires a mobile phone number.

You may be wondering where I got that quote from. It actually comes from an article that explains a PayID data breach that happened late last year. Funny how that works, huh?

Hopefully you can see where I’m getting at with this. If someone has PayID set up, then you can transfer money to them via their phone number. You also use that very same phone number to get in touch with them. This means that Vishal only needed to find a phone number used for PayID, pay them, then text that very same number. He didn’t need the BSB or account number in the first place.

3. Returning the Money

Pre-requisite: None.

Goal: ???

This step occurred on “our” end, so we know what happened. Vishal reached out to Kenji and took advantage of his goodwill, and Kenji made the transaction to return his $30.

What we don’t know is what Vishal was trying to achieve by getting Kenji to make this transfer. Clearly it was a necessary step, otherwise Vishal would’ve just taken all of the money without initiating contact. Sending $30 to Vishal somehow enabled him to consequently send himself the rest of Kenji’s money, but we don’t know how. At least, not at this stage.

4. Claiming the Loot

Pre-requisite: Authority/authentication to transfer funds.

Goal: To transfer the rest of the funds out of Kenji’s account.

This is where it gets a bit dicey.

Recall step 2, where we assume Vishal found Kenji’s phone number from a PayID data breach. Chances are, he also found other personal details, like his name and the last few digits of his card number. You know, the ones that no one seems to think are sensitive enough to hide. Armed with this information, Vishal would have likely been able to call up the bank and make a transaction. I imagine the conversation would go something as follows:

Bank Representative: Hi, how can we help you today?

Vishal: Hi, I'm Kenji. I wanted to set up a direct debit, could you help with that?

Rep: Sure, I'll just need to ask a few questions to make sure it's really you.

Vishal: Sure.

Rep: What are the last x digits of your card?

Vishal: xxxxxx.

Rep: Great, and could you tell me about a recent past transaction?

Vishal: Sure, I sent Vishal $30 not too long ago. The transaction ID was xxxxxxx.

Rep: Thanks! So which account would you like to transfer the funds to?

Vishal: To Vishal, please. Do you need the account number and BSB again?

Rep: No, that should be fine. Could you give me the details of the direct debit?

... ... ...

Banks typically ask for a recent transaction as a form of authentication, and this is why I figured Vishal may have wanted Kenji to make that initial deposit. This way, he’ll have the details of a recent transaction even if he doesn’t have access to Kenji’s bank account. That would be enough for him to ring up and impersonate Kenji, to set up a direct debit or bank transfer on his behalf.

Unfortunately, Kenji told me that the bank confirmed that no one had called pretending to be him, so there goes that idea. I wasn’t back at the drawing board for very long though. Rereading the Wired article I linked above reminded me that all the information we know Vishal has—phone number, and last few digits of card number—are generally visible on most online services. Try logging into your own Google, Apple, Amazon, or whatever. You should be able to find these tidbits in seconds.

Now the question is how did Vishal get into one of Kenji’s accounts to take this information? Again, I don’t know the exact answer here. There are plenty of ways to steal someone’s password, and we don’t even know which service(s) were compromised. That being said, I do have some ideas, but as before, it’s all just conjecture.

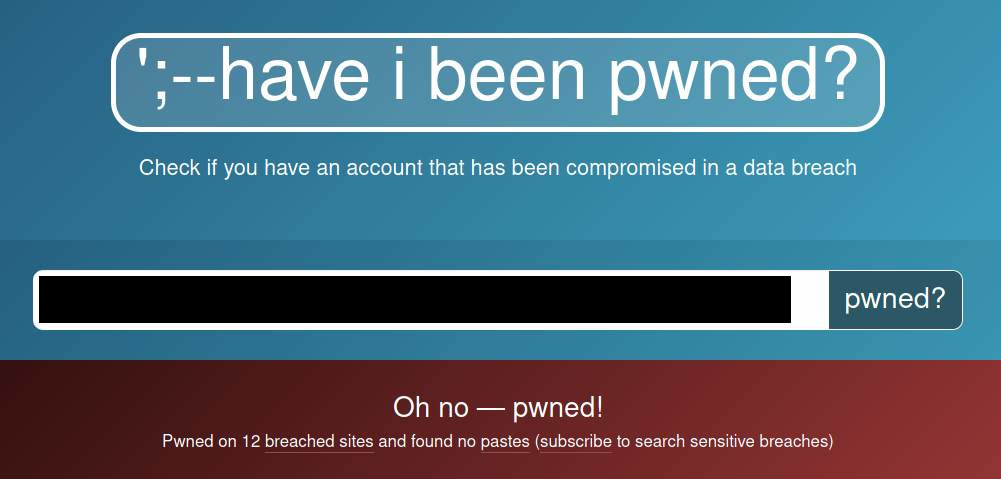

I know that Kenji uses an extremely weak password, and he reuses the same password on a plethora of services. There are probably alarm bells going off in every security-minded reader’s brain right now, and for good reason. He may as well have no password. I’ll save the password best practices for another time (in the mean time, check out the password safety billboards in Harajuku), but I have another good reason to believe one of Kenji’s accounts could be easily compromised:

I got him to throw his email into the trusty haveibeenpwned, and sure enough, the results were positive. This neat little app lets you enter in your email address and it will tell you if your credentials have been previously found in a password dump (i.e. from a company getting breached). If you get a positive result here then you may as well throw that email address away. Needless to say, I’m quite confident it would be extremely easy to gain access to one or several of Kenji’s accounts. Including his internet banking account.

So assuming Vishal had access to Kenji’s internet banking account, all he needed to do was log in and send himself the money. If that’s the case, then I’m not sure why he needed Kenji to send him back the $30 from step 3 in the first place. I have some ideas, but none of them are particularly convincing.

My first thought here was that it might have been to get around multi-factor authentication. I know that some banks require MFA for the first transaction to a new payee, but don’t for subsequent ones. So even if Vishal could log into the account, he couldn’t make a transaction without the MFA device. Turns out Kenji doesn’t use MFA though, so perhaps not. Or maybe he does, and just doesn’t realise it.

Some banking apps require a one-time password sent via SMS upon installation, but send future OTPs to the app directly and enter them automatically. Kenji claimed that he didn’t see a push notification of the sort either, though. Maybe the user is only prompted for MFA on large transactions to a new account, but making a small transaction once is enough to bypass the MFA requirement for future transactions? I feel like I might be grasping a bit at this point. A little experimentation with a friend could probably solve this one.

Alternatively, sending the money back to Vishal may have revealed some kind of information that he previously didn’t have, but needed to make the transactions. These payment logs are largely nondescript as far as I’m aware, but depending on the institution, I wonder if they might include a BSB and account number. If we go by the assumption that Vishal sent the $30 via PayID, then he might not have known Kenji’s BSB and account number initially.

To my knowledge, this information alone isn’t enough to draft from an account. Otherwise your friends and company could easily just withdraw money from your account based on the payment details you gave them. That said, Wikipedia seems to indicate that you can debit an account given the BSB/account number. Official sources seem to agree, but I didn’t bother confirming what additional information you might need to do so.

I’m really not too sure about this one. Barring Vishal having an 0-day on major Australian banks, sending someone money should be a completely safe action that doesn’t leak anything sensitive. If you’re reading this, “Vishal”, I’d be very interested to hear how you did this. There’s a link to my Twitter on the homepage.

Anyway, I’m no lawyer so I don’t have any advice for Kenji in terms of how to best go about getting his money back if the bank doesn’t cooperate. I am a security engineer though, so I can definitely give recommendations to fix all of his bad practices to hopefully prevent this from happening again.

1. Trust no one

It goes without saying, but if anyone ever approaches you unexpectedly and asks you to do something for them, don’t take them at their word. Personally I would just ignore them, but at the very least, do your spot checks and make sure you’re confident they are who they are. This goes doubly so when it’s anything money-related.

In this case, there were a lot of red flags right from the get-go. No bank would advise a customer to contact another customer to try and resolve matters privately. Giving out a customer’s phone number would also be a huge violation of policy. Kenji did pick up on this, but unfortunately let his good side get the better of him.

2. Throw away the bank account

It’s clearly been breached. I wouldn’t trust any money going in or out of that account anymore. Close it and open a new one. Preferably at another bank that actually gives more than 1% savings interest, but that’s a different discussion.

3. Throw away the email too

Same reason as above. It’s compromised, don’t trust it. Make a new one and update all of your important services. It’s a lot of effort upfront, but access to an email inbox will give attackers the opportunity to reset passwords for the majority of services. Lock it behind a wrought-iron fence made of tigers.

4. Change all your passwords

Your password is garbage and it’s the same on all of your accounts. If they guess it once (easy) then they have access to everything else for free. Start with your email addresses and money-related accounts, then go down in order of importance. Give everything a unique and secure password. And don’t tell me your password. Why do I know your password?

On a related note:

5. Use a password manager

Sign up for Bitwarden* and get it to generate a new password for all of your services. Keep using it for everything you sign up to. It will also remember all of your passwords for you so that you don’t have to. Using a password manager is probably the single best thing you can do in 2020. That conversation is out of scope of this blog post though, so you’ll just have to take my word on it for now.

*I don’t actually use it myself and I’m not sponsored by them, but as far as I know, it’s the best open-source and normie-friendly password manager.

And that’s all from me. This is the first time I’ve actually been interested in reader input, so I’m slightly regretting not implementing a comment feed now. I’m sure that will be short-lived though, so go hit me up on Twitter if you have anything you want to share. Goodbye.