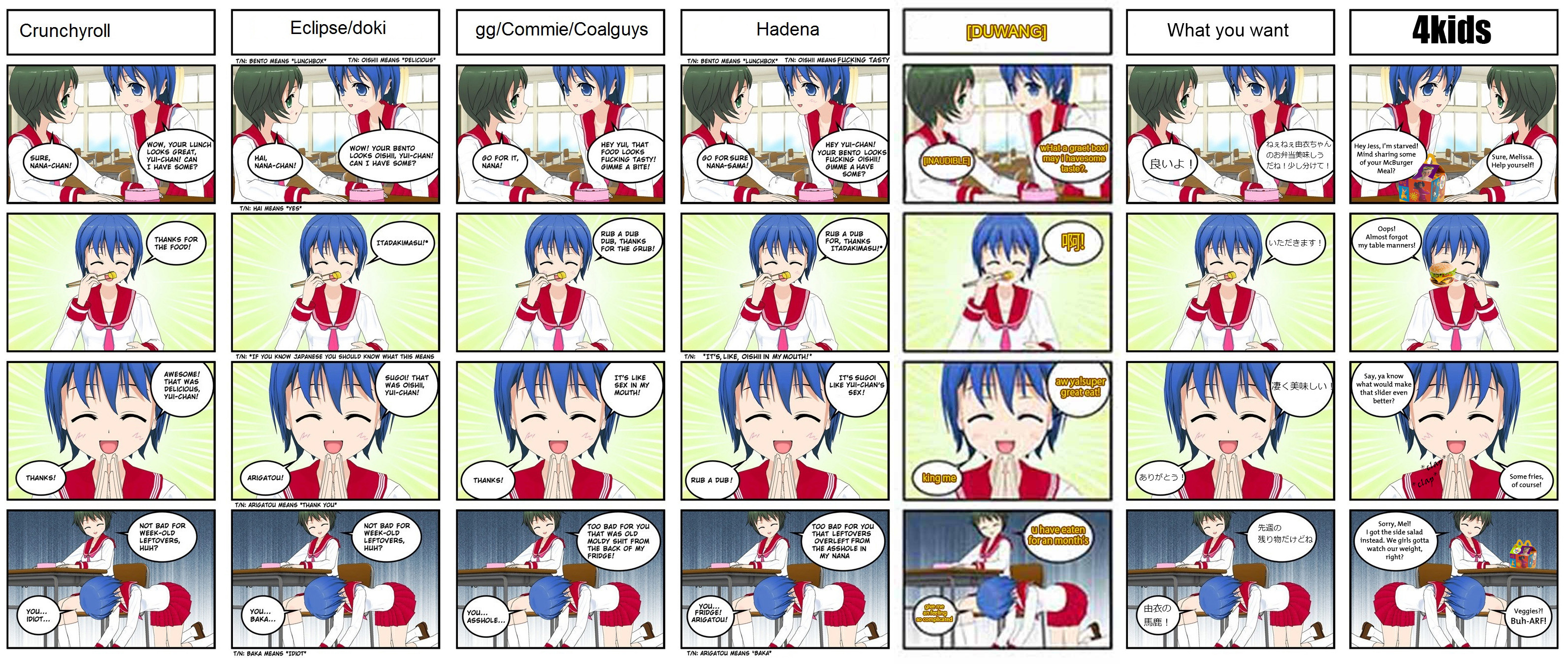

Whether or not honorifics should be preserved in a Japanese translation is a discussion as dumb as it is old. I’m not going to take a side on this one though, because there’s an even dumber argument out in the wild. “Honorifics are required in translations to convey meaning” is undoubtedly one of the most asinine claims I’ve ever had the misfortune to witness, and it really needs to be addressed.

Honorifics are all but one tiny facet of describing one character’s relationship with another. I feel like many consumers have prized these small tidbits of Japanese that they can understand, and now imagine they are essential to the material when the author simply chose to use the ones most appropriate in context rather than as the deep, intricate tools of language that English readers make them out to be.

For example, people love to talk about the amazing differences between the personal pronouns that characters use. To the author though, it’s the crudest way to introduce a character’s basic personality and character elements, which are then fleshed out via actual prose. No author would tell you they were pouring their heart and soul into choosing a character’s personal pronoun because ultimately, it is of extremely little importance beyond its use as a convenient identifier amidst the lines of unattributed dialogue.

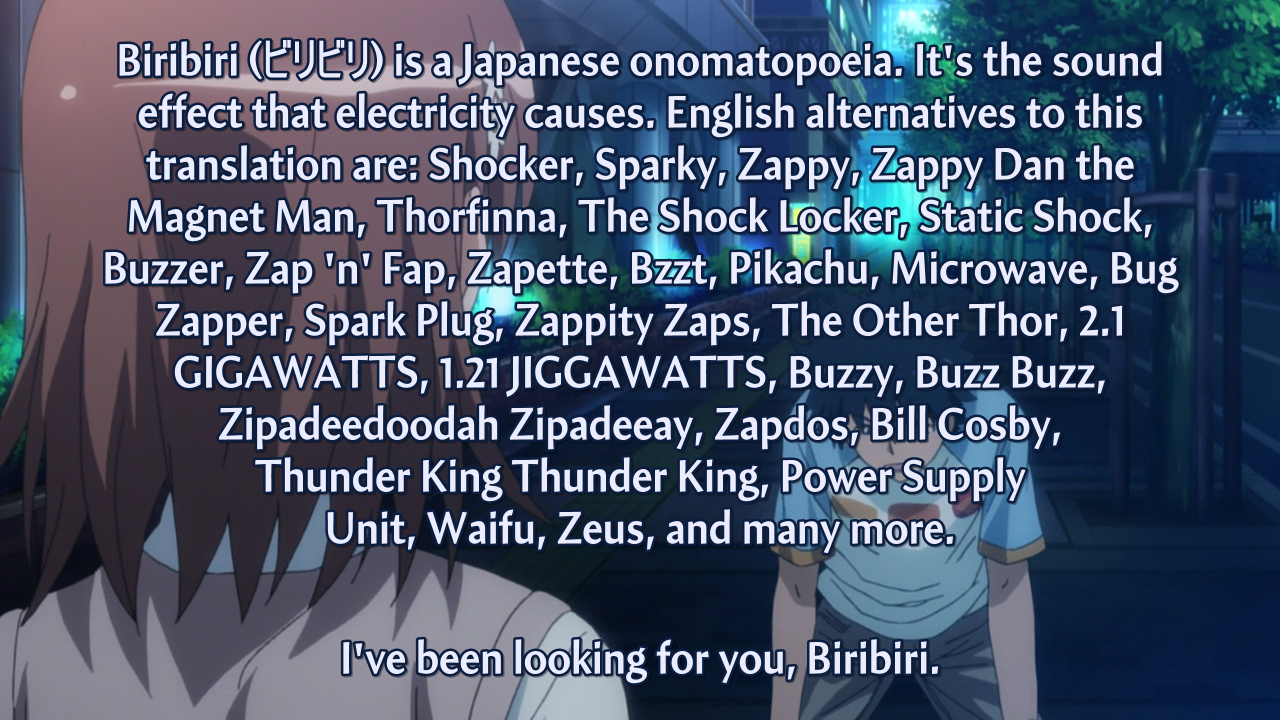

This is also true of honorifics. The relationships that honorifics define can’t be discerned from the honorific alone. A good example of this is “senpai”. The argument that there is no English equivalent is a popular one, but the fact of the matter is that it doesn’t matter.

A “senpai” is your superior, but that doesn’t mean anything on its own. They could be your mentor, someone who is firm but fair with you, someone who teaches you and nurtures your abilities and growth but isn’t afraid to put you down where your peers might be hesitant or concerned about their relationship with you. They will be your superior by virtue of age or status within your shared institution, and will have no qualms about teaching you the right thing. Many will try and help you by drawing on their greater experience, or by doing something for you that only they could do via means unavailable to you. They can be good or bad, but an active one can have a major impact on your life whether it be at school, work, or even in life in general. They can be objects of respect, fear, admiration, learning, and affection—or hate.

The thing is though, you can’t glean any of this by only reading a line of dialogue where someone is addressed as “senpai”. All of the aforementioned nuances only come about in the prose and context that surrounds the characters. The honorific terms of address provide little to no additional information. The author doesn’t choose to have a character call another “senpai” to emphasise these points, they choose to do so because that’s the natural way to refer to someone, exactly the same as calling someone by their name in English.

There’s too much leeway within the term of address to discern anything meaningful about the relationship between characters from the honorifics alone. This must be done through the prose, and therefore can be explained without honorifics.

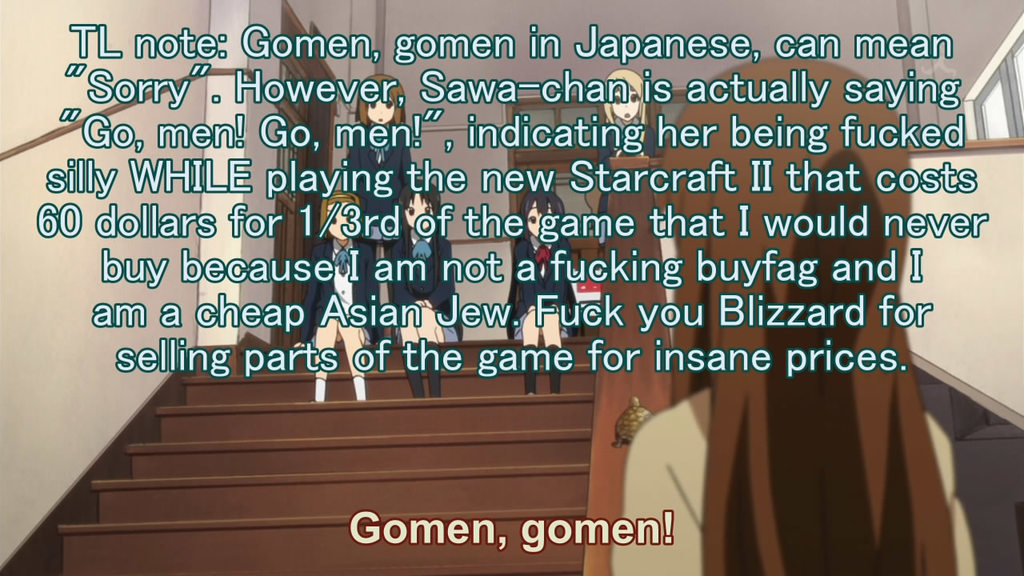

This is true for all honorifics, and really, all terms of address. Of course, I’m not saying that they have no meaning at all. If someone is addressed as “-sama”, then they’re probably important—or being ridiculed over their arrogance. See, even in this general example, it’s impossible to know without context. If someone is addressed as “-sensei”, they could be a teacher. Or they might be a doctor, an author, or some other kind of respected expert. If someone is addressed as “-kun”, then they’re probably a boy. Unless it’s at school or work, in which case it could be a girl. They’re also probably younger than the speaker, except when they’re not. You see?

None of these honorifics provide any information on their own that can be demonstratably known without context. All of the important identifying information is in the prose. There is no way to discern anything about the relationships between characters with certainty by knowing only the mutual honorific terms of address they use with each other.

There aren’t many kinds of situations where honorifics are absolutely necessary and critical to understanding the work. It would have to involve a piece that is heavily ingrained in Japanese culture, with plot points that revolve around honorifics, or that offers social commentary or criticism on the nuances of human relationships in a uniquely Japanese way, that relies on Japanese honorifics to convey. In an edge case like this, the argument for preserving honorifics may hold some weight, but most of the time there isn’t a good reason to do so. In your average battle manga or slice of life romcom, the prose is what defines the complex relationships and overall context of the work, not the honorifics. The author’s intentions can be entirely conveyed with prose alone.

Honorifics are simply an easy shorthand to refer to certain archetypes that have been developed over time in Japanese society, and by extension, in Japanese literature and media. They are not required to impart nuances of character relationships, and anyone that thinks otherwise has no idea what they’re talking about.

[02:05] <Myaamori> you know I wonder why all the japanese concepts that weebs argue are untranslatable are always entry tier japanese

[02:05] <Myaamori> probably just a coincidence, I'm sure there are no more advanced japanese concepts that would be tricky to translate

Addendum: this post is largely lifted from a comment by AsiaExpert. I took the liberty of rewriting it on my blog for the sake of preservation and presentation.